One can mess around on google search for a few minutes with a handful combinations of the words: abs, core, training, exercise, weightlifting and come out with a core exercise list like below:

Hanging leg raise, V-ups, Plank, Standing twist, Hanging leg raise, Sit-ups, Plank, Russian twists, Weighted sit-ups, Jack Knives, Ab Wheel, Hollow Rocks, Reverse Crunches, Crunches, Russian twists, Side planks ...

The list of "core" exercises available for people to try are endless. Some pick their "favorites" and stick to them. Some try all of them. While some come up with their own exercises and add to the list.

As the list keeps growing, so does the frustration of the people trying them. And that's because

Most don't really see any noticeable impact of doing these ab exercises to their resting posture or weightlifting numbers.

Ever wonder why that is the case?

It is not because "everyone is different"

It is not because "each exercise has a different difficulty level".

It is not because their coach didn't pick the right one for them.

The two main reasons why for most, one or more of these exercises never feel right or hurt their lower back or rarely give them the "core strength" they are looking for are:

- Their understanding of the core is incomplete. And consequently,

- They treat their core as a "black box".

An incomplete intellectual understanding will always result in an incomplete, and thus inefficient neuromuscular control of the body or a part thereof.

And as we saw earlier, practicing an inefficient or incomplete control during training will only make it more permanent and "default" increasing the risk of injuries and blunting both short and long-term performance.

And when one treats something like a black box and are told that its protection is of utmost importance, the best they can do is "brace" it with all their might. (adding to their never-ending list of isolated cues that they rely on during training).

Understanding Core

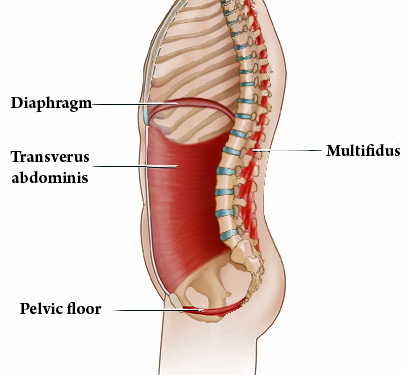

The human midsection or core is best understood in a bottom-up and inside-out way. Bottom-up because it enforces the connectedness of the limbs to the torso (and thus the upper body) via the pelvis.

Inside-out because the deep layer of muscles is the first line of defense against external resistance. And for one with proper control, an intention for movement or exertion is enough to recruit these muscles, before superficial muscles come into play.

The pelvic floor muscles (PFM) supports the bladder as well as the reproductive organs and connects the inferior aspect of the innominates (hip bones) and the sacrum. Inability to contract the PFM will cause the pelvis to move inappropriately during motion.

The Multifidus (MF) muscle is located along the back of the spine. Note that it lies deeper relative to the Erector Spinae muscle and is the spine's first layer of protection and consequently its "first aid" for stability during movement.

Finally, the Transversus Abdominis (TVA), is the innermost ab muscle which "completes the picture" by aiding thoracic and lumbopelvic stability (via compression of ribs and viscera). Its innervation by multiple nerves makes it a crucial muscle as it allows the CNS to recruit the muscles in the extremities efficiently.

The PFM, MF and TVA work in cooperation (via cocontraction) for the lumbar spine, sacroiliac joints, and the bladder to be stabilized properly. These three muscles stabilize the low back and pelvis before any actual movement of arms/legs.

The Diaphragm (which is the main muscle of respiration) and specifically the manner in which one breathes as well as their self-awareness, has a tremendous impact on stabilizing the spine and the core in general. That, however, is a bit out of scope and will be discussed in a separate post.

And finally, it is worth noting that

The superficial abdominal muscles such as rectus abdominis, erector spinae, internal & external obliques obviously are useful, but their role in assisting with postural integrity is secondary when compared to the deeper core musculature.

Bracing works, for some

Revisiting the popular bracing advice that a lot of athletes are taught, which is to "pressurize the abdominal cylinder" by breathing into their belly and compressing that air, we see that it is both right and "wrong" (or more like, it doesn't apply).

And that is because while the instruction is sound, the execution of the same is drastically different for people with and without the ability to recruit the above key muscle groups.

For most of the time, what is not told beforehand, is the following truth

Being able to control the three key muscle groups above, along with other fascial components in the abdominopelvic and thoracic cavity provide one the means through which the cavity can be pressurized. As the "caps" of the cylinder are glottis at one and the pelvic floor on the other end.

Hence for someone without such control, the same act will only give them a superficial protection and a "disconnected" feeling during movement. As neither the PFM are recruited (letting the pelvis "dangle in the air") nor the TVA involved (causing only partial motor control of limbs).

On the other hand, a holistic recruitment of these muscles is not only a superior way to protect your spine but also ...

A safe and efficient autopilot mode, you can rely on during lifting or movement.

An escape route from constant, isolated cueing.

And finally, the key towards being able to implement the tenets of integrated movement and reach an ultimate athletic state.

Continued in part 9

References

Training for the deep muscles of the core, Diane Lee

Wikipedia: The Multifidus muscle

Wikipedia: The Transverse abdominal muscle